It's Time for Law Firms to Start Loving and Leveraging Data

Challenges of Data Management

Law firms, and the lawyers that practice within their walls, often have a love-hate relationship with data. This dichotomy is not surprising.

Taking the "hate" side of the ledger first, law firms are increasingly tasked with managing more and more data. That data, which can come from a variety of sources, including clients as well as that generated by the firm itself, comes in myriad forms and formats, each with its own idiosyncrasies and vulnerabilities.

That, of course, can lead to several daunting challenges for firms. For example, the sheer volume of that data and the sensitivity of much of that data — especially when it's emanating from firm clients — makes law firms attractive targets for hackers and denial-of-service attacks.

In addition, the volume and diverse nature of the data managed by law firms — be it client-originated files, data generated through standard network applications like Excel or Word, information associated with accounting and financial software, records stored on firm intranet systems, websites supported by the firm, records residing on firm-created proprietary databases — carries with it its own set of costs, such as data storage and disaster recovery redundancy, as well as the costs associated with the staff and vendors needed to oversee an ever-growing ocean of information.

From the perspective of an individual practitioner in a firm, this vastness can lead to the view that there is simply too much data to manage in an effective manner and that no one has a clear view of what mysteries might lurk beneath its surface.

And, because this data might not be organized in an optimized fashion, those practitioners and administrators in the firm inclined to use the data to enhance their decision making — and effectively manage risks — often find themselves in an endless loop of analysis paralysis, never really having the confidence in the data they wished to use to inform their decision making.

The True Issue: Data Quality

The ever-increasing quantity of data and newly emerging forms of data are not the true sources of these challenges facing law firms. Indeed, with the increasing availability of technologies employing artificial intelligence and machine learning, law firms have access to powerful tools that can already manage and provide insight into vast quantities of data.

For example, the power of the tools used to conduct electronic discovery has changed dramatically over time, allowing attorneys to assess volumes of data today that would have seemed unfathomable just a few years ago.

Moreover, by harnessing the power of machine learning and related technologies, practitioners today cannot only review more data in a given amount of time than they could before, they can also more readily locate and identify significant documents sooner in the litigation process, which in turn provides for better, fact-based decision making over the course of the litigation.

No, quantity in and of itself is not the issue. Instead, it is the quality of the data — or more precisely, the lack of quality data, i.e., good data — that lies at the heart of the challenges facing law firms.

Quality problems with data can arise from any number of causes, including how the data has been gathered — often using inconsistent sets of instruments — or how it is measured, often using a shifting series of metrics and benchmarks. These issues are especially apparent in a major source of firm data, litigation.

The Importance of Structure and Good Data

The litigation process lacks a coherent and standardized structure around which information can be organized in a consistent and systematic way, and without a standard structure that ensures common metrics and benchmarks, industry participants will continue to struggle to utilize fully and effectively the technologies needed to meet increasing client demands for the efficient delivery of litigation services.

Firms that recognize the fundamental importance of structure to the litigation process — and to the data associated with it — and then act to provide that structure are in the pole position to utilize existing tools to deliver, track, measure and assess litigation training, case management, billing or timekeeping, the value of work product, and, ultimately, outcomes.

The ability to create, organize and exploit good data has never been more important for law firm survival. Even before firms had to grapple with the effects of COVID-19 on their operations and consider new ways to provide client service through a dispersed workforce, law firms needed to harness the power of good data to be successful.

Leveraging Technology for Strategic Decision-Making

For example, as more and more existing and potential clients employ a request for proposal process to award work, law firms need the ability to understand the costs associated with providing their services so that they can make metric-driven decisions about how and what to bid for that work.

Similarly, the increasing prevalence of corporate clients relying on a panel counsel approach — where corporations narrow down the number of law firms previously used to a smaller, discrete set of providers — means that law firms must have a thorough understanding of how they provide legal services and the value of those services.

Furthermore, access to reliable information in which decision makers have confidence can provide a firm with valuable insight into how the firm's resources are being used to create work product, and the value of that work product.

Through such insight, firm leadership can make metrics-based decisions about how to staff projects — i.e., finding the right mix of partners, associates, paraprofessionals and other service providers to meet internal firm objectives and goals, as well as to stay within budget constraints imposed by alternative fee arrangements — and better allocate scarce firm resources while simultaneously managing risks and expectations.

The Path Forward: Good Data and Technology

Currently available technologies tend to address this need in one of two ways.

Some proffered solutions are based on analytics derived from task and activity codes used by practitioners to record their time. These technologies collect the data that has been entered and then afford the decision maker the opportunity to slice and dice historical data to predict future project costs on similar matters.

The theory behind these tools is that armed with sufficient historical data, a reasonable prediction, i.e., a prediction within acceptable bounds of risk to the firm, can be made about the cost (and potential profitability) of future work. In considering this method, great care has to be taken to ensure that the underlying data is collected at the level of specificity needed for this purpose.

For example, time and task information that permits timekeepers to assign their work to overly broad categories, e.g., L120 — Analysis and Strategy of the American Bar Association's Litigation Code Set, may lack the precision needed by today's practitioners because users might be tempted to lump otherwise discrete and measurable tasks under one, easy-to-use code.

In other instances, a code set that categorizes tasks too narrowly can result in false distinctions being made between or among tasks or lead to inconsistent coding by users.

Similarly, it's also important to consider the extent to which time has been assigned to particular tasks and activities on a consistent basis. Inconsistencies in this regard undermine the usefulness of relying on past matters to guide future decision making.

Furthermore, practitioners ought to consider the degree of flexibility offered by these systems when it comes to manipulating the data so that they can test various approaches to performing work.

For example, some technologies permit users to compare and adjust various configurations of inputs — e.g., the percentage of time to be spent by partners, counsel, associates and paraprofessionals on the potential new matter, or where the work will be performed, or whether third-party service providers should be considered for discrete tasks — to gain insight into internal resource management and the impact of that management on profitability.

Other technologies eschew the reliance on a specific set of time and task codes and instead use software based on natural language processing to organize data for use by decision makers. Under this method, software can examine the underlying data — in this instance, narrative timekeeping created by attorneys and staff — and then sort it into discrete tasks with assigned values to those tasks.

As was the case when considering a solution based on task and activity codes, practitioners thinking about selecting this option need to assess the flexibility of the tool when it comes to data manipulation in order to assess various options when responding to a request for proposal or entering into an alternative fee arrangement.

Practitioners should also consider assessing the accuracy of software when it comes to categorizing the narrative descriptions created by various timekeepers. One way to do this would be to borrow an approach often used in electronic discovery matters, where practitioners have been using natural language programming to categorize discovery materials for some time now.

There, users typically sample data sets — in this case time records — to determine the degree to which the software is accurately categorizing the data. A similar approach can be considered in this context to avoid the age-old problem of garbage in, garbage out, i.e., an incorrect or poor-quality input will produce faulty output.

Good data, grounded on a standardized structure, is the fulcrum by which law firms can leverage powerful technologies to understand and exploit the information they have and create. Possessing this capability is of increasing importance to law firms as they compete not only with other law firms for client work, but face growing pressures from other professional services firms, including the Big Four accounting firms, for that work.

The creation, management and strategic exploitation of good data can be a powerful value multiplier and differentiator for law firms, practice groups and even individual practitioners. The mastery of data can significantly enhance the value of the firm, practice group or practitioner to clients by improving their ability to show value for money (i.e., legal spending) in the provision of legal services, especially when compared to competing service providers who can only offer vague notions of the cost of work.

Similarly, data proficiency provides users with needed insight into internal costs, resource allocation and profitability, thus enabling them to engage more effectively and with less risks in alternative fee arrangements with clients. In short, because good data is essential to reliable, consistent, metrics-driven decision making, the ability to create, manage, organize and understand that data is of increasing strategic importance to law firms as they navigate the ebb and flow of their industry.

Indeed, because good data is essential to survival, law firms need to assess their current state regarding data — e.g., how much they have, where it is stored, who created it, who is using it, who is currently managing it, and how it is secured — and take the steps needed to move from simply having data to being able to create, operationalize an act on good data.

For many firms, the path forward will present a classic make-or-buy question: Will firms devote internal resources to develop the structured systems needed to manage and foster the use of good data, or will firms use an acquisition strategy to acquire the structure, processes, tools and expertise needed to meet their good data needs?

Firms have often faced similar questions when considering an expansion of their practice portfolio or geographic reach, so it's reasonable to consider the real possibility that future law firm acquisitions and mergers might be driven, at least in part, by firms recognizing their own strength and weaknesses with respect to where they are on the good data spectrum and acting to bolster their position through strategic acquisitions.

We began this article by observing why law firms and practitioners often take a dim view of data. Given the current state of much of that data, as well as its volume, that perspective is not at all surprising or revelatory.

Conclusion: The Power of Organized Data

What is revealing is that data, when properly organized by a standardized structure and leveraged through the use of existing technology, can become the good data — the actionable data — that law firms and practitioners need to manage their cases more effectively, recognize the value of their work product, and make metrics-based decisions with a high degree of confidence that benefit both the law firm and its clients. With such potential, we should all show good data some love!

Article originally appeared in Law360

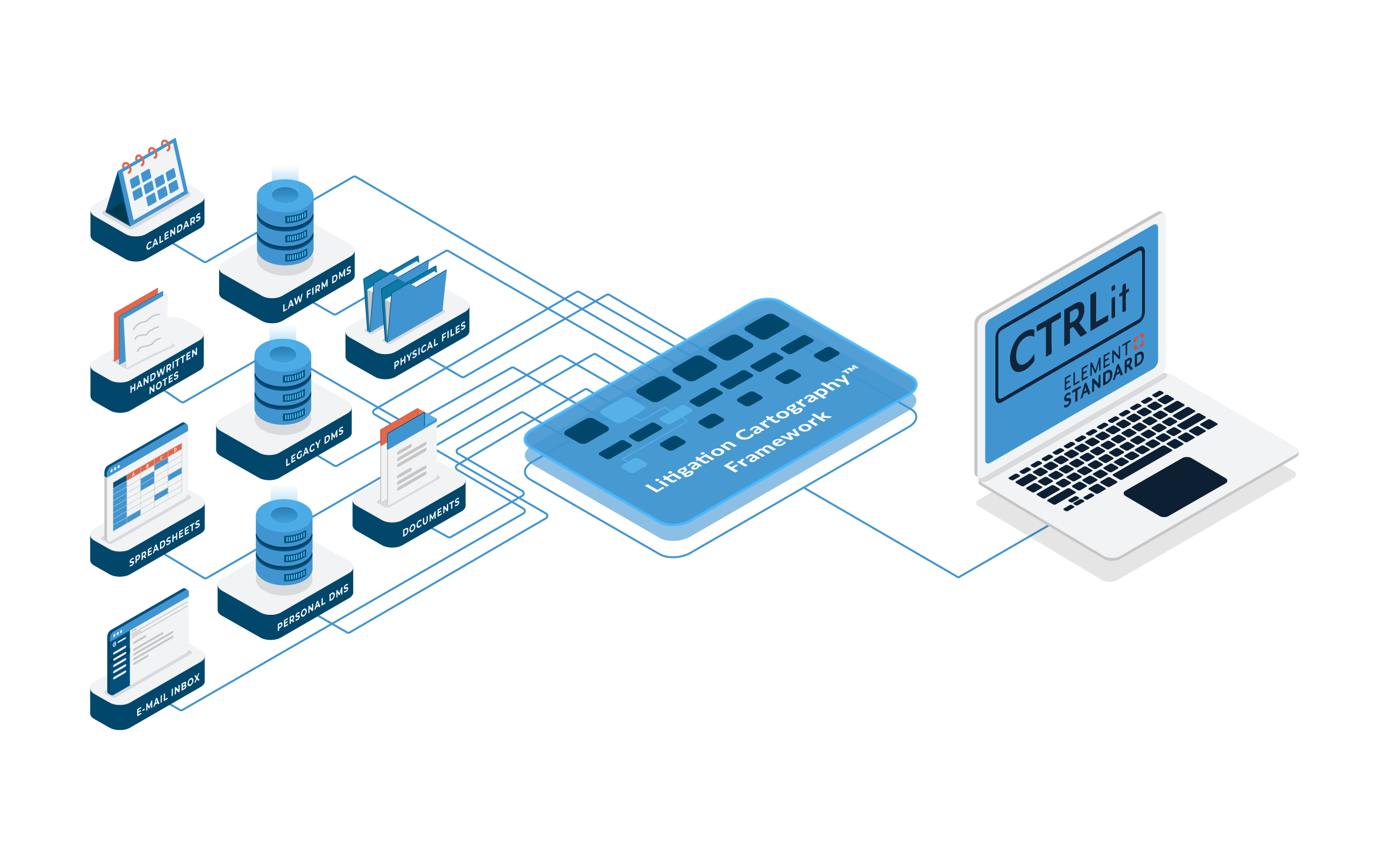

Add Some Control to your Litigation with CONTROLit™

Discover how CONTROLit™ can streamline your process and eliminate junk draw litigation forever.