How In-House Counsel Can Better Manage Litigation Exposure

Litigation takes a lot of time and energy to handle well. So how can the in-house counsel succeed when both are in short supply and acquiring more is terribly expensive?

During the economic downturn 12 years ago, enterprise legal departments learned that even as litigation volumes increased, there was internal pressure to reduce costs and increase efficiency.

Will the same trend emerge in 2023 as we approach another difficult economic period? Or is it already emerging?

Unlike the teams faced with that crisis, today's legal departments are better equipped to handle these competing pressures because many have new leadership to assist navigating them, namely legal operations.

However, in-house litigation counsel will still struggle to juggle the conflicting demands of confidently managing more cases, and controlling the increase in litigation exposure, with fewer resources.

But which specific resources that affect litigation outcomes will be in limited supply? And how might a general counsel and their in-house litigation counsel leverage those resources more effectively?

The most obvious is budget, even if it's not terribly impactful to determining litigation outcomes on its own.

The most cliché is to remind us all that data is a resource. Accumulation of data enables evidence-based decision making throughout organizations, giving leaders the tools to mitigate or overcome myriad cognitive biases.

Fascination with budgets and data, however, has obscured the import of a crucial resource in unlocking any value in the measurement of prices and the parsing of data: the attention paid to it, both in quantity and quality.

A simple illustration highlights this fact. Take for example a quarterly litigation spend report that shows a 20% decrease in litigation expense. At the end of most quarters, the report will be praised. But when a case leads to an increase in potential exposure many times more than the straight-line savings in spend, praise turns into questioning why more was not done to mitigate the exposure, which means questioning why more was not spent.

And if the opportunity to regain control has long since passed because the appropriate attention was not paid to the available data indicating the looming risk, the same report becomes Exhibit 1 that the mere existence of an aggressive budget and mountains of data is inadequate to effectively manage litigation.

Thus, the true struggle for an in-house team is allocating a very limited and valuable resource — their attentional resources. And today's challenge is being prepared to do so in a way that contributes to better control over the coming increase in the volume of litigation and keeping a lid on the resulting exposure to their companies.

In advertising and marketing, there is already widespread recognition of the importance of attention as a source of economic value.

Engagement from microtargeted groups drives the advertising revenues of companies like Meta Platforms Inc. and Google LLC. Sports broadcasts are prized by advertisers because the intensity of focus their fans bring far exceeds that of casual viewers.

Social media influencers command significant salaries because they circulate marketing messages in a semi-organic environment to audiences who are already predisposed to engage with it. Businesses depending on the resale of attention constitute "a global industry with an annual revenue of approximately $500 billion," according to Tim Wu's Blind Spot: The Attention Economy and the Law.[1]

In each of these examples, attentional resources can be measured not just in terms of quantity — the sheer number of accumulated hours of engagement — but also by the quality of attention paid.

The importance of the quantity or quality distinction is buttressed by contemporary work in social science. In "Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow," the celebrated psychologist Daniel Kahneman finds across a wide range of studies that human beings are essentially cognitive misers.[2]

When thinking fast, human beings use mental shortcuts that enable quick and effective judgment without deep, reflexive deliberation. The use of these shortcuts is the trunk from which branches of cognitive bias — precisely the tendencies that the use of data is meant to address — grow and spread.

Importantly, however, simply pushing employees to pay more attention is at best a failing solution, and at worst magnifies the problem. Thinking fast is an inevitable part of human cognition, and more efficiently capitalizing on attentional resources requires designing systems that nudge employees away from cognitive biases, ensuring that they're still productive when they're thinking fast.

And just because litigation is complex doesn't mean everyone involved in the litigation industry stops thinking fast when dealing with it. For the in-house counsel, managing litigation exposure requires a lot of attention.

It's why it's so attractive to buy into the idea that measuring one aspect of exposure — litigation spend — can be the panacea that achieves the best outcomes for the company. Spend is a simple measurement that allows for fast thinking to feel effective, plus it achieves an outcome shared by other stakeholders — saving money — that, as discussed already, is nearly always praised.

But every litigator knows that measuring one or two factors, no matter which, cannot achieve the best outcomes. Allowing incomplete information to dictate decisions at vital junctures is indicative of a cognitive bias, constructed to make quick decisions and to avoid the insecurity of not having full knowledge of the factors in play.

Experienced litigators know that it is their understanding of the complex factors of litigation and managing them at key moments that delivers the best outcomes, no matter if fast or slow thinking is applied.

In-house counsel, whether flush with outsized budgets or seeking to do more with less, also know that the wins come from mastering litigation's complexity.

The solution then is not avoiding the complexities but instead building systems that focus attention on where it can be most effective in delivering better outcomes. What is required is developing better mental shortcuts, not eliminating those shortcuts or distilling them into a false panacea.

One way to achieve this is to build workflows that offer employees choices that simultaneously simplify the problem confronting them, while naturalistically reflecting the actual cost and benefit calculations they are making. A well-designed process can present employees data framed in terms that enable them to easily recognize various tradeoffs and choose between them with the benefit of context.

For example, comparing litigation strategies between three law firms can be difficult. With myriad unknowns, an in-house counsel may get three strategic explanations that, while individually convincing, are as difficult to quantify and qualify as three works of art from three different centuries.

But if that same in-house counsel presented a checklist of case goals to each counsel along with the request for case strategy, the beginnings of a more reliable process would begin to form. The same explanations from each firm would then be anchored to some context and the tradeoffs between them would be more apparent.

Whether such workflows are put into action via a checklist, a calendar schedule, a spreadsheet, a piece of software or a combination of them all matters less than the ability to reliably invest attentional resources to the process over time.

The alternatives to better designed systems are both undesirable — either:

• Decisions faced with maximum complexity, quickly depleting the attentional resources of your workforce and ensuring uneven work product in the short term, and burn out and turnover over the long term; or

• Decisions faced with key elements stripped out, leading to choices that are cognitively biased and fail to effectively take advantage of available data.

If either of these alternatives is the reality in which litigation decisions are being made, the in-house counsel will see what little control they have eroded rapidly as litigation volumes increase.

In-house counsel hire outside litigation counsel to mitigate litigation exposure. Legal operations professionals and their in-house litigation colleagues need tools that empower them to allocate their attention at the most impactful moments in the litigation life cycle, and to make decisions — defensible decisions — that account for the complex reality of litigation, no matter the outcome and no matter the spend.

The competing pressures of managing more with less are not as challenging to overcome when systems are designed to recognize the importance of managing our limited attentional resources.

Only when these dueling realities — the complexity of litigation and the necessity that we

rely on our fast thinking — are merged through the application of better process design, can in-house legal departments and their outside litigation counsel collaboratively make their lives better, and achieve the best and most defensible outcomes for their mutual client.

[1] Tim Wu, Blind Spot: The Attention Economy and the Law, 82 ANTITRUST L. J. 771 (2019).

[2] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux (2011).

Article originally appeared in Law360

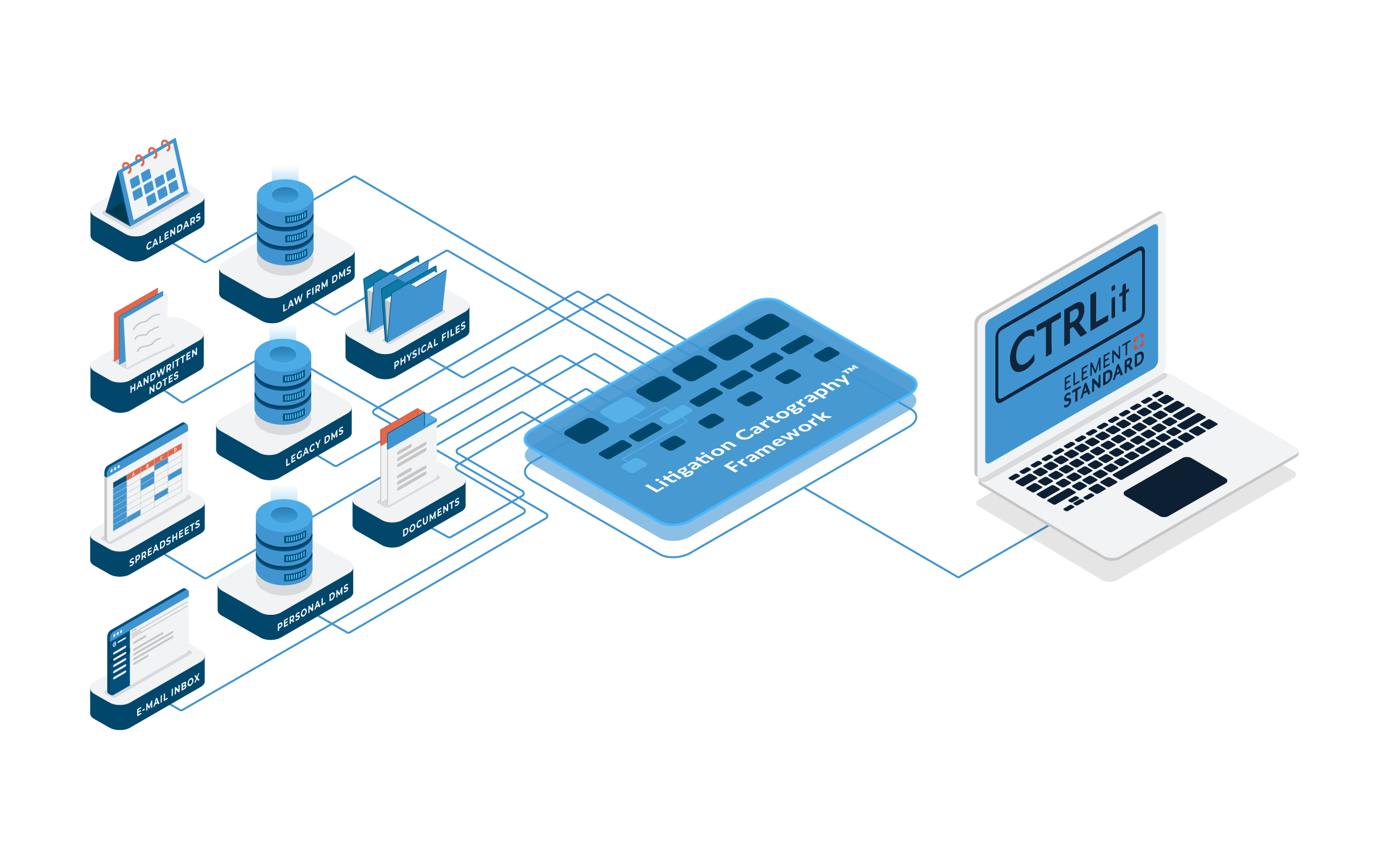

Add Some Control to your Litigation with CONTROLit™

Discover how CONTROLit™ can streamline your process and eliminate junk draw litigation forever.